Sparsha Puja in a Mental Institution called modern society

When life changes profoundly, you might forget it all began with Sparsha Puja.

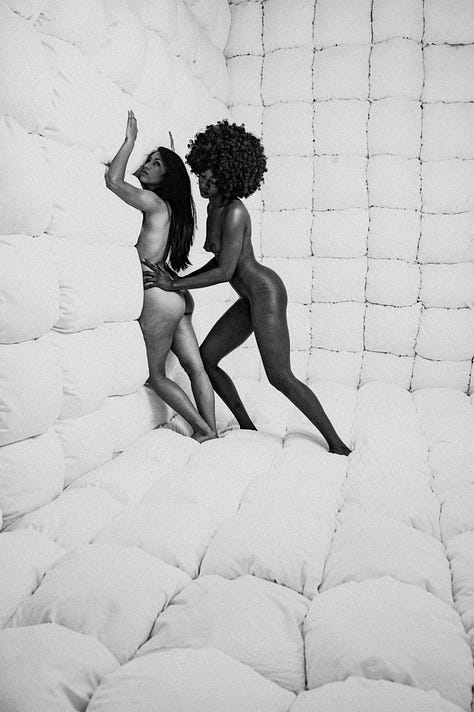

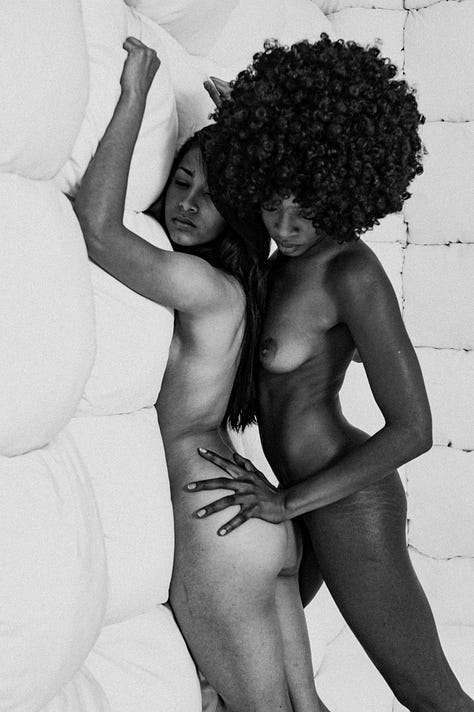

Look at the photographs. Two naked bodies moving in slow motion, staring without blinking, breathing in patterns that make no biological sense, touching each other for hours with the intensity of surgery and the tenderness of madness. You could call it erotic. You could call it therapeutic. You’d be missing the point either way.

We live in a mental institution. We call it civilization. We wage wars between nations while waging the same wars inside our own skin. The mind attacks the body for its desires. The body rebels against the mind’s tyranny. The intellect tries to organize what can’t be organized. Families fracture along the same fault lines as countries. Everyone’s trying to control, suppress, transcend, or fix something that was never broken to begin with.

Sparsha Puja doesn’t heal this. Healing implies something’s wrong. This practice does something else entirely: it remembers. It takes two human beings and drops them back into the state we were in before we learned to be at war with ourselves.

The techniques look absurd because human beings look absurd when we’re not performing civilization. Standing three meters apart, moving toward each other for fifteen minutes while maintaining eye contact and breathing like we’re hyperventilating in slow motion. Rubbing bodies together for twenty minutes like animals who forgot they’re supposed to be embarrassed. Pressing someone against a wall and slapping them while they breathe. Lying over your partner like a spider, staring without blinking, neither of you allowed to look away.

These aren’t sex acts. They’re not dominance games. They’re not therapy. They’re techniques for dismantling the civilized performance, the split between what your body knows and what your mind insists on, the war between your biology and your ideas about your biology.

The breath patterns are key. Manda Kapālabhāti, the slow forceful exhalation done for minutes that become hours, operates directly on the nervous system without asking permission from your thinking mind. You can’t maintain your usual defenses when your breath is doing something this irrational. The boundary between you and your partner starts to dissolve not because of some mystical transmission but because the physiology of separation gets interrupted.

And the touch. Viddhaka, Udhrishtaka, Gharṣātaka. Experimental touch that has no goal, no technique, no “doing it right.” Your hands learn to feel without agenda. Your skin remembers it’s an organ of perception, not just a boundary keeping you separate. The person touching and the person being touched start existing in a field that predates the subject-object split we’ve built our entire reality around.

What actually happens during Sparsha Puja happens in the Citta, the deep unconscious where your personality gets constructed and maintained. The practice works on the Vṛttis, those mental fluctuations that keep you trapped in the same loops of reaction, defense, desire, and aversion. Not by suppressing them. Not by “integrating” them. By exposing them to conditions they can’t survive: sustained presence, irrational breath, touch without agenda, eye contact without escape.

The Yoga Sutras say Yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ. Yoga is the cessation of mental fluctuations. Most practices try to still the mind by fighting it. Sparsha Puja stills the mind by making the usual fluctuations irrelevant. When you’re standing naked across from another human being, moving one centimeter per minute, breathing in a pattern that makes your nervous system choose between transformation and collapse, your usual mental stories about who you are and what you need and what you’re protecting simply… stop mattering.

The effects don’t show up immediately. You don’t leave the practice “healed” or “enlightened” or even particularly changed. The work happens in the unconscious, in the genetic memory, in layers of conditioning that took generations to build. You might not notice anything for months. Then one day you realize you’re responding to life differently. The wars you were fighting, internal and external, have somehow lost their urgency. Not because you won them. Because you remembered what you were before you learned to fight.

Some practices promise transcendence. Sparsha Puja offers something more dangerous: return. Return to the state where your intellect and your biology aren’t enemies. Where your sexuality and your spirituality aren’t separate categories that need to be integrated. Where your shadow isn’t something to conquer but simply energy moving through a body that’s learning to stop resisting its own existence.

The practice looks extreme because human wholeness looks extreme in a society built on fragmentation. It looks sexual because we’ve forgotten that touch is a sense organ, that skin knows things the mind can’t access, that bodies in contact bypass the usual defenses that keep us performing our approved roles. It looks irrational because it is irrational. Rationality is what got us into this mess.

Sparsha Puja is anthropological self-discovery. Not in the academic sense. In the sense that it drops you back into the human animal’s original knowing, before we learned language sophisticated enough to lie, before we built civilizations complex enough to require that lie, before we split ourselves into the parts we’re allowed to show and the parts we have to hide.

This is why it’s one of the twenty main Puja rituals worth preserving. Not because it’s ancient, though it is. Not because it’s exotic, though it appears that way. Because it remembers something we’ve forgotten: humans aren’t crazy. The mental institution we’ve built and called society is crazy. The wars between mind and body, intellect and instinct, spiritual and carnal, self and other—those wars are the pathology, not the cure.

When two people practice Sparsha Puja, they’re not working toward some future state of integration. They’re remembering a past state of wholeness. Not personal past. Species past. The knowing that lived in bodies before bodies learned to be ashamed, afraid, or apologetic for existing.

That remembrance doesn’t fix anything. It doesn’t make you better. It makes you real.

And in a mental institution, reality is the most dangerous medicine available.